14th May, 2025

Well, I suppose the time has finally come to post this piece of fiction online. This piece was my undergraduate creative dissertation for my creative writing degree. It was written between the October of 2022 and the May of 2023, and I remain incredibly proud of it to this day.

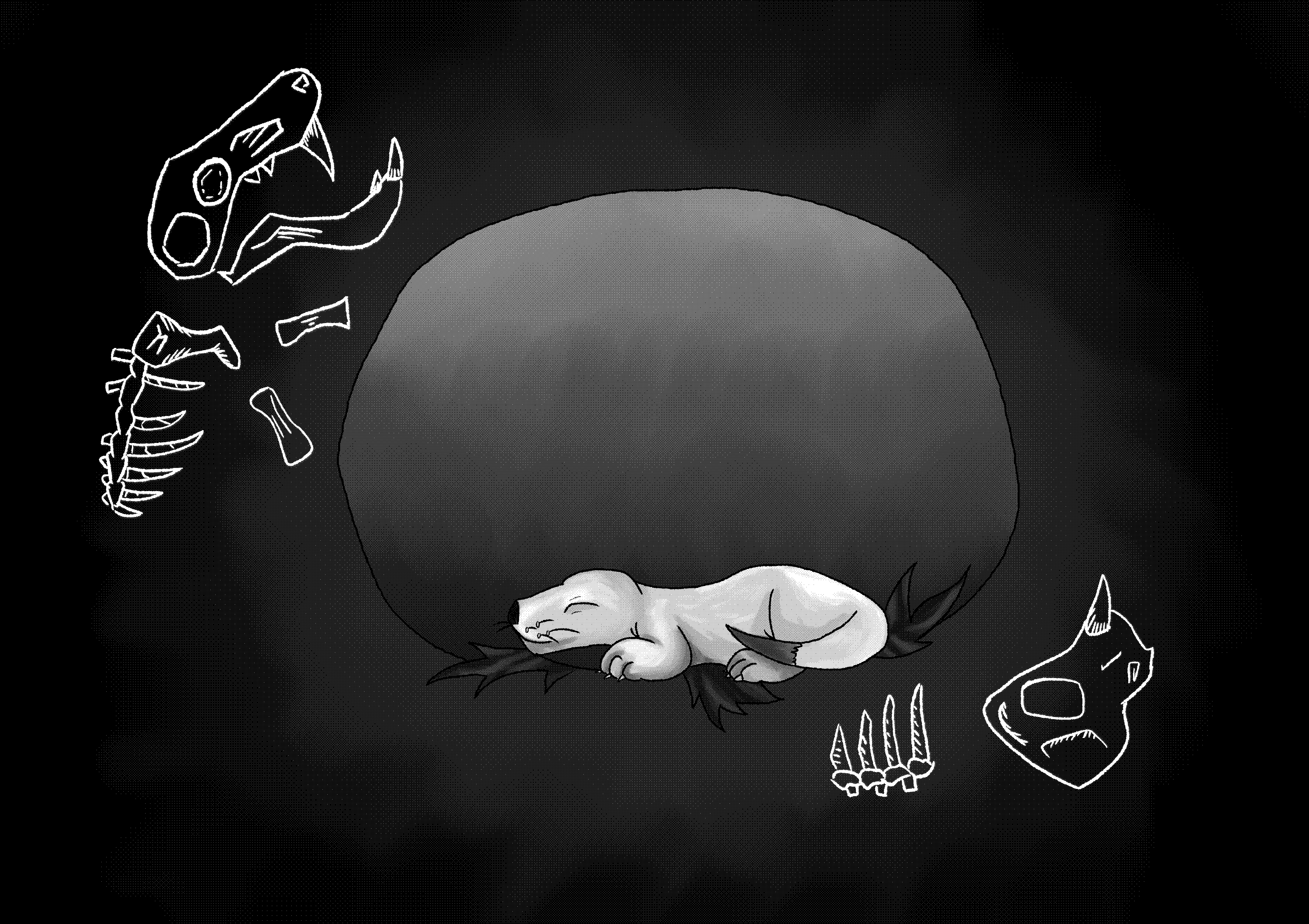

The illustrations here are the ones I submitted with the dissertation, though one of these days I would love to create a version with higher quality drawings.

Included at the bottom of the story is the creative commentary I wrote for my dissertation, complete with original footnotes and bibliography.

"Someone will remember us

I say

Even in another time."

- Sappho, Fragment 147, trans. Anne Carson

The Karoo

The Triassic, 250,000,000 BC

Broomistega found herself sighing wearily. The cool black mud of the creek bed had once been soothing against her skin, but now it was almost all dried up. She had watched it as she laid there as the sun drew high in the heavens, deep fissures growing in the creek bed as if it were the scaly back of some great creature. The only bit still wet was directly beneath her, under her not inconsiderable belly. But it had begun to irritate her soft skin, so she thought it about time to move on.

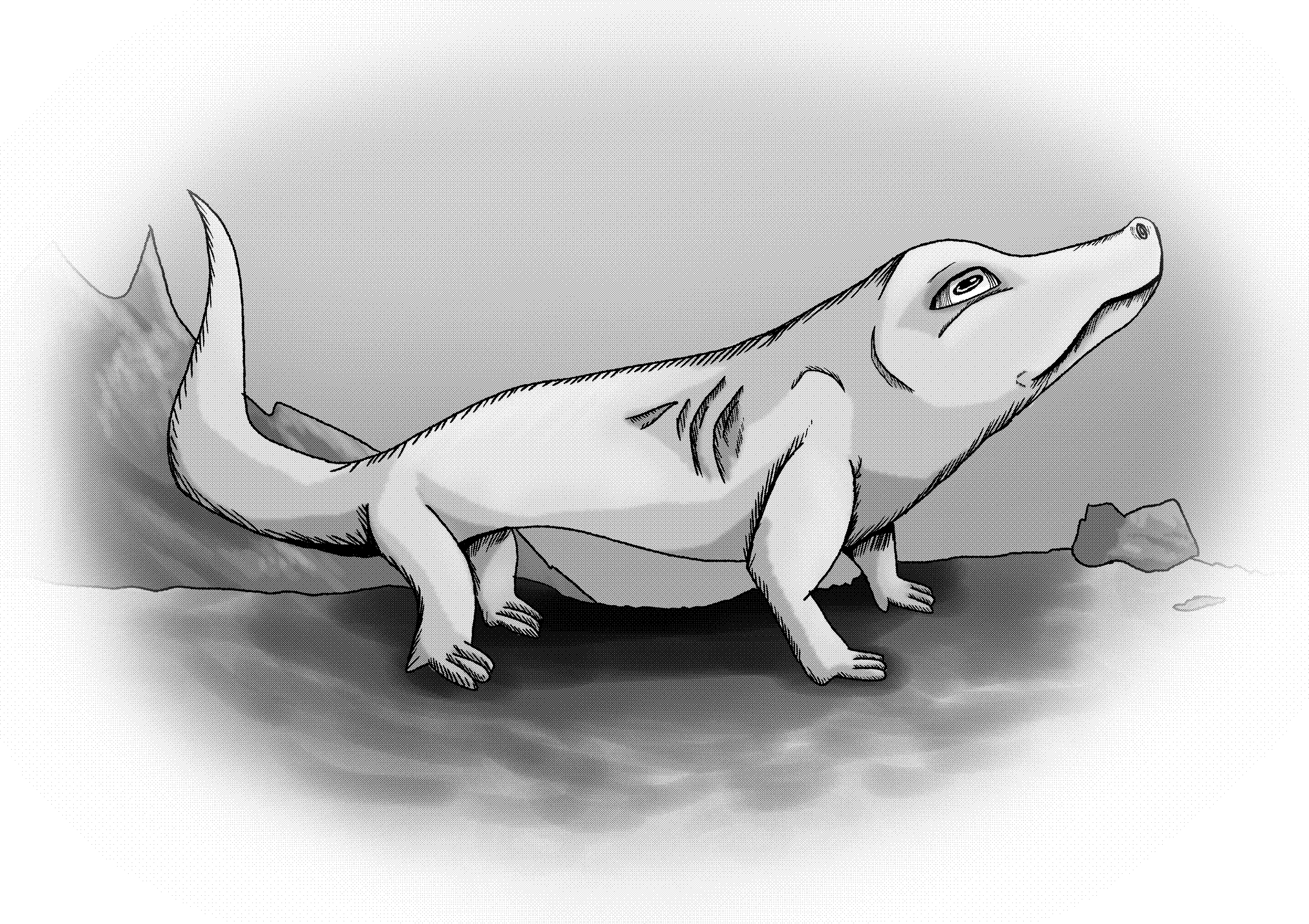

She was not a large animal, which was typical of her breed; the fat and supple-skinned folk who lived on the margins of water and land. Not yet fully grown, there were barely two handfuls of her in size. She was a sort of mossy off-green in colour, and dappled with specks of yellow and dark brown. Her eyes were similarly mottled, and placed peculiarly high upon her broad-snouted head, above a mouth filled with little curved needles perfect for snatching whatever morsel that should happen to wander into her line of sight. But the little morsels were gone now, and so were most other things. The dry season had chased all of them away, leaving only hot red soil and withered plants in its wake.

And what a stupid thing it was, that the world should die for months at a time in the heart of the year. She thought of her spawning place, where the same green waters that would rush so softly over her skin had smoothed all the stones into pleasantly rounded plates. Even if she could remember quite where it was, could she find it? Or had the dry season turned it too into the same dry orange waste as the rest of the world?

Rain, she thought as she rose up onto stocky little legs, mud squelching between her curled-up toes. What she wouldn’t give for just a little rain. The rushing of water. The cool satisfaction of drinking it in through her mouth and through her skin. Perhaps she could follow the river to its source, up through the heat haze and to a place that the dry season hadn’t touched. A place where plumes of algae still rose in ribbons from the cool depths. A place where silvery fish still dashed and darted, waiting so patiently for her to catch them. A place where she could still hope to find the deep calm of her spawning lake.

The broad crescent arc of her stride was broken by a familiar ache in her right side. She stopped a mere ten paces from where she had lain, cursing beneath her breath. She had known many scrapes in her short life, falls and grazes and near-misses with scoundrel predators, but only one had marked her quite so intimately. The hulking Erythrosuchus had not been mobile enough to chase her outright, so it had trodden her beneath its heavy feet before trying to wrench off her head. It was weeks ago now, but the pain was still fresh.

She took a deep intake of breath before proceeding once more, spluttering on the dust she had kicked up. Though the noonday sun was white-hot and glaring, she could just about make something out on the horizon. Upriver from the dried-up mud was a tall cone of greenery, swaying slightly in the meagre breeze. A cluster of plucky young glossopteris trees, somehow still green and supple against the heat, with the promise of cool shade beneath their leaves. Her hope renewed, she darted for them, ignoring her pain through gritted teeth.

Nieu Bethesda, South Africa

The Anthropocene, 1929 AD

Jimmy took a swig from his canteen, before pouring the rest on the dry ground before him. That flint was coming loose whether it wanted to or not, even if he had to pry it from the earth with his own two hands. It would make a fine addition to the shoebox of treasures that lived under his bed.

His hands were small, with fat fingers that couldn’t always do quite what he wanted them to. But then again, he was just a small boy. It was for that reason that he wasn’t allowed the axe from Father’s tool shed, which could’ve done the job in a minute flat. Mother had been appalled that he’d even asked for such a thing, but Father had ruffled his hair and laughed.

“You’ll ruin the edge on it, Jim. Scraping around with it in the dirt like that.”

It wasn’t fair because it didn’t even have much of an edge on it to begin with, and he only wanted to play with it in the yard. He would’ve taken the shovel, which Mother said was fine since it wasn’t sharp, but since the handle was almost as long as he was tall, he figured that it was more trouble than it was worth.

He knelt down and poked at the puddle he had poured. It was just sat there, on top of the dusty red earth, not soaking the soil as it should’ve done. He patted it and then looked at his palm, seeing only the stray specks of earth it had picked up.

It was then when he remembered something that one of his scoutmasters had once said at Junior Meerkats, during their trip to float model boats on the old Gats River. While the earth may look thirsty in the driest days of summer, it is quite unable to drink. The water just sits on its surface and slides away. It pools and gathers and… And he’d stopped listening at that point because Bern Thompson had dropped a stink beetle down his collar. It was something to do with mudslides, perhaps.

His nail beds burned as he scratched in the dirt for his prize, but it didn’t take long for the earth to give it up. He was soon victorious, the flint clasped in the grubby grip of his right hand. Satisfied, he rose to his feet and returned to the house.

But as he passed over the threshold, he was greeted by an unfamiliar figure. It was a grey-haired old man, tall and broad and pinkened by sunburn. A dark blue blazer was draped over the crook of one arm, and the white shirt he wore was rumpled and sweat stained.

“Ah! The young Jim!” he said, smiling warmly. There was a twang to his voice that took the boy a moment to place. Was he Scottish? “Your father has told me so much about you.”

Jimmy could feel warmth spreading across his face. He clenched his rock tightly in his hands.

Father appeared from the kitchen, his round sunhat pulled high across his head. “We have lemonade if you want some, doctor,” he said. “Jim, this is Dr Broom from work. He, uh… He’s interested in your special rocks.”

“M-My rocks?”

Jimmy opened his balled-up hand and passed the flint to the old Scotsman, who graciously accepted. He produced a pair of round tortoiseshell spectacles from the breast pocket of his shirt and put them on, bringing the small rock to his eye to scrutinise it.

“Ah yes, a flint. You can find fossils in these, you know. Tiny little ones. To think, how many precious specimens must have been carved up to make flintlocks.”

“Fossils?” Jimmy asked. “Like… Dead animals?”

“Extinct animals,” the Scotsman replied. “And I didn’t come to see flints. Your father says you have a rock in your collection with lots of little holes in it. Like nothing he’s ever seen, he said.”

“My pumice stone?”

The doctor gave a soft laugh. “I have reason to believe that it’s more than a mere pumice. Go and get it for me.”

Jimmy ascended the stairs to his bedroom, considering the prospect. There was a chapter in one of his books about fossils. Or dinosaurs, rather; ferocious creatures who once roamed the earth. The book was on the cheaper side, so the creatures were rendered in unnatural hues against the yellowed pulp-paper pages; a powder blue Tyrannosaurus stalking his yellow Triceratops prey, while placid pink Edmontosaurus gathered in herds to sip from their watering hole. But in his mind’s eye he could see them, exactly as they were. The greens and browns and greys of their tough hides. The vibrations of their heavy footsteps. But they were gone now, leaving behind only fragments of their greatness. Mere bones. The idea of holding one in his own two hands made him more excited than he’d care to admit.

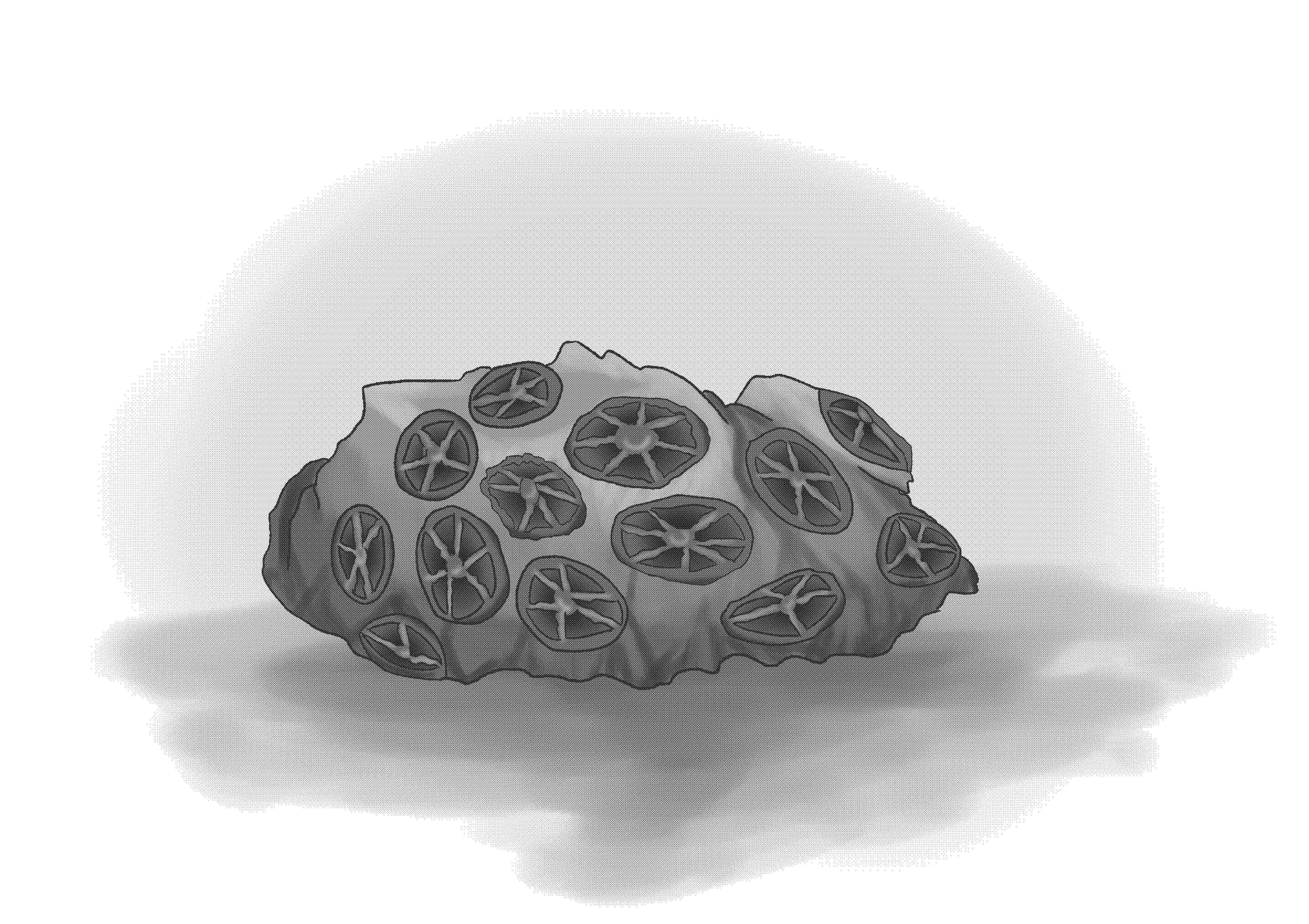

He pulled his shoebox out from under his bed and removed the lid. The pumice was wrapped in a handkerchief because it seemed rather fragile, and he took great care in unwrapping it. It was a rather innocuous looking stone; chalky grey in colour, softly rounded in shape, and deceptively lightweight for its size. It was covered all over in at what had once seemed to be little rounded pits, which he had cross-referenced against the black-and-white photo plates in Father’s geology book to identify it as a pumice, but under greater scrutiny that label didn’t quite seem to fit. The pits were not the uniformly round and deep ones of the photo, but broad and shallow cups with star-shaped protrusions in their middles. The Scottish doctor must be right, he thought. This rock was special.

When he returned downstairs, Doctor Broom was sat at the dining room table with Mother and Father, sipping politely at one of Mother’s unpleasantly warm lemonades.

“Out in the dirt all the time, he is,” she was telling him. “Bringing home his little treasures. He’s a bright lad, but you do worry, don’t you?”

“There’s a career in it if he’s lucky,” Broom replied.

“He’d like that, I think,” Father added, pushing his own drink aside. “If it pays well.”

All three turned to look at him as he entered. Silently, he shuffled his way towards them, placing the handkerchief-clad stone on the table.

Broom took it between his thumb and forefinger, giving a deep contemplative hmm as he lifted it to his eyes. He scrutinised it closely for just a moment.

“It’s a tad dirty,” he frowned. With one hand he removed his glasses, using one of the lenses as an impromptu magnifying glass.

“Oh, I didn’t want to wash it,” Jimmy replied, words coming out a touch bolder than intended. “It’s just that it looks… Looks like the water would damage it, with all the little holes.”

The doctor gave a wry smile. “Good lad, good intuition on you. It’s porous, the water would damage it.”

Finally, he placed the stone back down on the table.

“Is it a dinosaur bone?”

“It’s a sponge.”

“Oh.” All that excitement, and it was nothing more than sponge?

“A very old one,” Dr Broom continued, “Potentially hundreds of millions of years old.”

Jimmy blinked in confusion. “There were sponges that many years ago?”

The doctor looked back at him, turning over the fossil in his hands. He narrowed his eyes for just a moment, and then gave a broad grin. “Oh, I see. No, it’s not a bath sponge. Well, technically it’s… A sponge is an animal. It lives in the sea. It has a sort of porous exoskeleton and…”

Father gave a cough. “So, it is a fossil?”

Dr Broom placed the ancient sponge back down on the table, before wrapping it up neatly in the handkerchief. “It is, and a very interesting one,” he said. “Mr and Mrs Kitching, young Jim, I was wondering if I could take this stone with me. Show it to some important people.”

Jimmy frowned. “Will I get it back?”

“I’m afraid not, son,” Dr Broom replied. “But you’ll find more. You have a knack for this. And I’ll make sure they all know it was you who found this.”

“Oh…”

“And you listen to me, young Jimmy Kitching,” Broom continued. “You have a gift, and it cannot go to waste. You could be the greatest if you keep it up. Promise me you will.”

Jimmy blushed. He looked at Dr Broom, and then at Mother and Father. All smiled at him expectantly.

“I promise,” he said quietly.

The Karoo

The Triassic, 250,000,000 BC

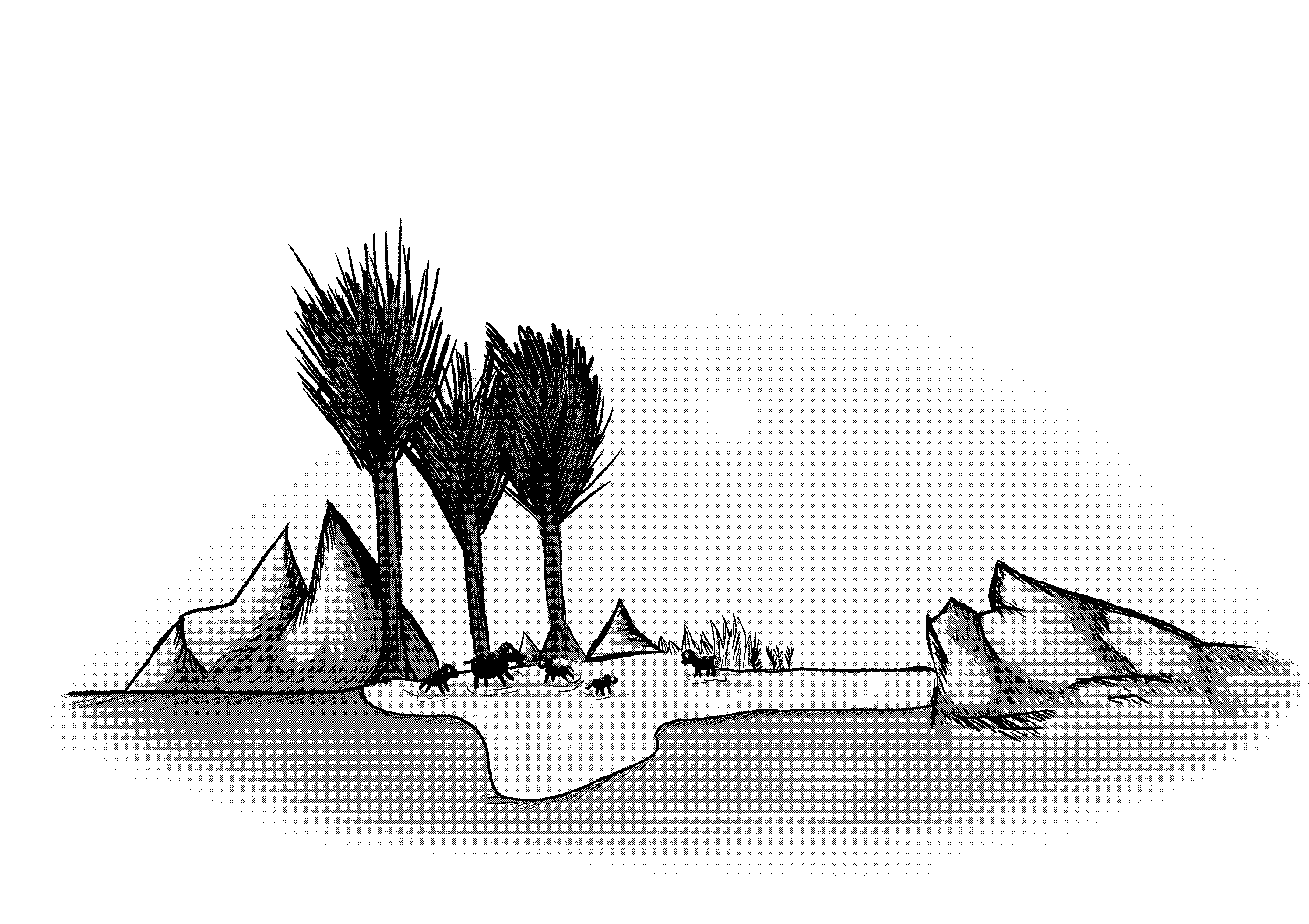

As Broomistega approached the glossopteris grove, she realised that she was not the first to have discovered it. There, wallowing in a precious shallow pool beneath the tree shade, was a small herd of Lystrosaurus. There was as many of them as she could count, which she had to admit was not very many, and then a few more on top of that. She squinted at them in the noonday sun, their bulky bodies warped by heat haze and ringed in white-hot halos.

That was a surprise, Broomistega thought. She’d seen so many leathery grey carcasses in the preceding days and weeks that she was beginning to believe the dry season had seen them all off for good. They were a plant-eating breed, with flat beaks and blunt tusks built to snuffle for roots in the dirt. Before the dry season had come, they were by far the most common creature she would encounter. Now they were a snack, if she could even get to their bodies before the sun baked their flesh beyond all edibility.

Broomistega blinked, and the halos vanished. A wizened old sow broke from the herd to appraise her, bowing her domed head and blinking her deep-set little eyes.

“Stagnant,” she said. “No good for drinking.”

Between the heat and the pain in her side, it took Broomistega a moment to find her words. She stood there with her mouth wide open, catching imaginary flies.

The sow gave a low snort. “Can’t you hear me, green thing? No drink here.”

“I’m… No need for drink, I just want to be wet,” Broomistega stammered, praying she’d be understood. “I’m hurt.”

The old sow looked to a yellow-tusked boar who was lying on his side in the pool. He gave a grunt of affirmation, and then rolled over.

“You can sit, but we’re watching you,” the sow said, beak gritted.

Broomistega stepped into the pool on tentative toes, wary of the many eyes looking down upon her. She settled in a spot where the water was just deep enough to lap against her back as the breeze stirred it, the algae smooth and soothing against her wounded side. She had not intended to fall asleep there, surrounded by so many strangers, but the exertion of the journey had gotten to her. She allowed just one eye to close, and then, inevitably, the other.

“As I was saying,” an old voice rasped. “It’ll end. It always ends. Four of em’, I’ve seen in my years. The wet can’t hide forever.”

There was a grunt of frustration, and then a splash of water.

“Hey!”

“Be quiet, old boar! What is there for us now? No grazing grounds, no nesting place. Just this pool and its tough old roots.”

“Pah! Be patient. Every day we spend in this mess is a day closer to…”

Then, suddenly, there was a rush of splashes and squealing. Broomistega’s eyes shot open just in time to see the herd spring to their feet and flee the pool. She turned her head sharply to see the reason why.

A lone Moschorhinus sauntered drunkenly towards them, oblivious to the chaos it had caused. It was at least three times Broomistega’s size, with a heavy jaw honed for the crushing of bones. But this one seemed weakened, almost pitiful. Its subtly striped fur coat was broken in places by deep weeping sores, leaving snail-trails of silvery fluid glistening across its back. And its eyes, no doubt once piercing, were a sickly sightless white. It sang as it sauntered; a discordant melody both wordless and tuneless. A grim requiem if ever Broomistega heard one.

She found herself freezing as it drew close. It could not see her, that much she was sure of, but it could strike if it heard even the slightest movement.

The ripples of its lapping tongue rolled through the pond as the ailing creature tried to drink, followed by a coarse splutter and shower of saliva as it choked on bitter algae. The old Lystrosaurus boar chose this moment to strike, arching his back and charging the beast with a guttural war cry.

“You go!” He barked, slashing at the air with his tusks. “You get out of here!”

Moschorhinus made a blind lunge, its heavy jaws snapping shut around nothing at all. In the moment of confusion, the boar landed a bite on the creature’s foreleg, and then at a fold of sinewed skin at the base of its throat. It was only a warning, but it still drew a crimson crescent of blood where his beak had sunken in, leaving the beast to skitter away with its tail drawn between its legs.

The boar grunted as the Moschorhinus disappeared behind the trees. He then turned to cast his withering gaze upon Broomistega.

“This is what I do to those who threaten us, green thing,” he said, his tongue sweeping across the bloodied edge of his beak. “I suggest you watch how you behave.”

Broomistega sunk below the water. She snorted passively, bubbles emerging from her snout in response.

Lystrosaurus Assemblage Zone, South Africa

The Anthropocene, 1975 AD

James Kitching mopped his forehead with his dirty sleeve, leaning hard against his shovel that stood arrow-straight in the dry ground. Under his watchful eye, the team had turned the red sandstone beds into a city of off-white windbreaks and deep square holes in only a matter of weeks.

But this was not the revolutionary expedition he had been hoping for. A hundred tonnes of shovelled earth had yielded very few animal remains. He could see them lying there on a canvas sheet from over the lip of his trench; the top half of a Lystrosaurus skull warped into an almost quizzical expression by a quarter-billion years of heat and tectonic jostling, and an unidentifiable ribcage still trapped in a matrix of tough grey rock. Both awaited being stored away in protective plaster wrappings, but he’d hesitated in doing so. It felt a bit too much like an admission of failure for comfort.

He sighed wistfully, yanking his shovel out of the ground with both hands. He struck it down again, hard into the earth with a sweeping stroke. Then came a sound. A resonant ping. He had hit something.

He dropped to his knees and began to work on it with the little hand trowel he kept tied to his belt. He knew it was likely nothing special, but it wouldn’t hurt to let hope thrive for just a few more moments.

“Found something, Jim?” An assistant called, leaning over the edge of the trench and peering down at him.

He struggled to look back at him, squinting in the afternoon sun. “Don’t you go getting excited. Just a boulder.”

The assistant gave a broad grin. “Your boulder has teeth.”

“What?”

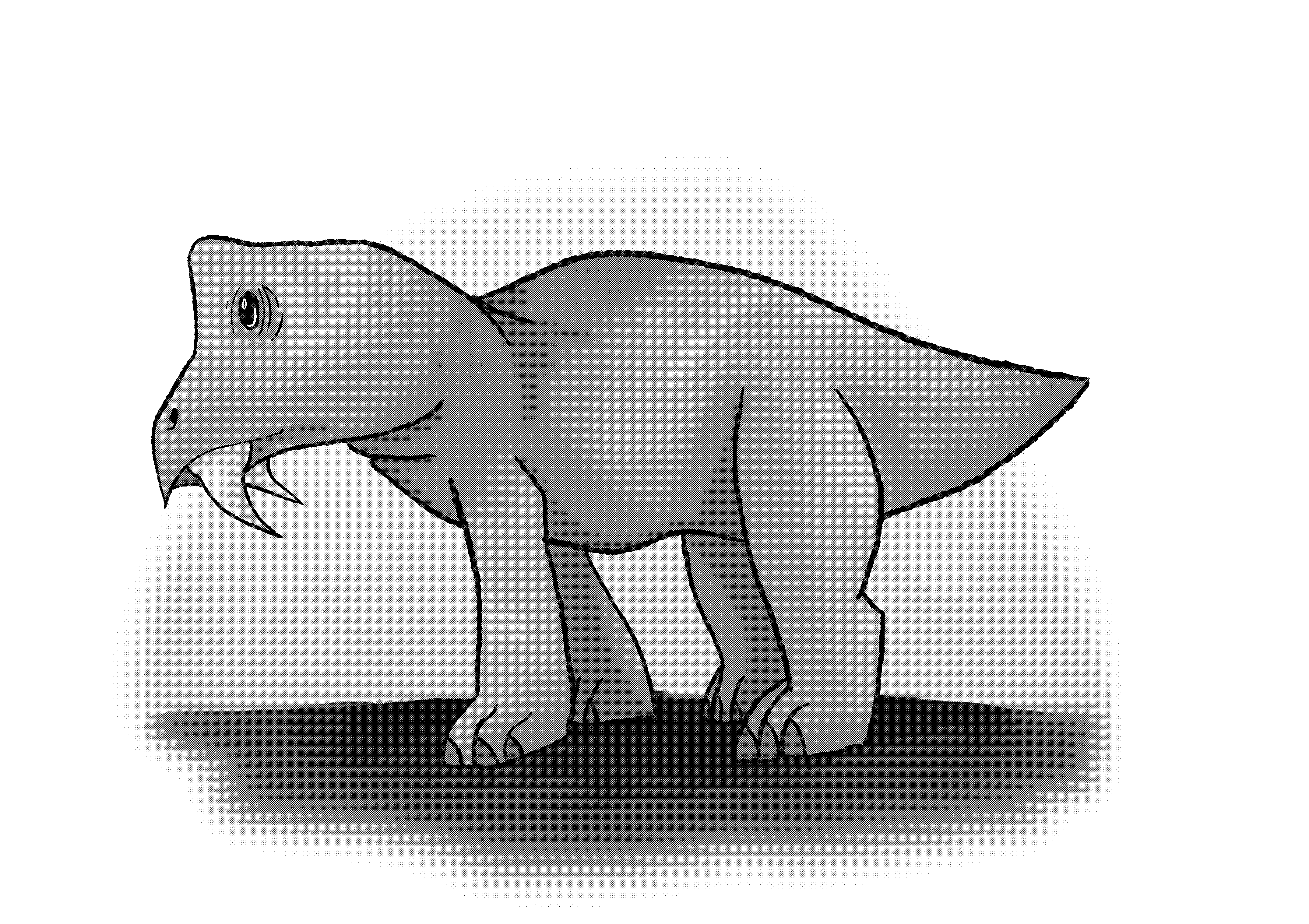

At a second glance he could see it; a black protuberance sticking out of the edge of the rock. It was the tip of a bony snout, complete with delicate teeth. Differentiated teeth, little peg-like incisors and a sharp canine fang, more closely resembling the teeth of a mammal than a typical reptilian jaw.

“A cynodont,” he said. “Galesaurus or… No. Thrinaxodon.”

The assistant hopped down into the trench. He ran a single outstretched finger across the smooth bone surface. “Y’think it’s a burrow cast? That the whole thing is curled up intact in there?”

Kitching reached for his trowel again, but then paused with the implement in his hand. He looked down at its curved blade, the way it glinted cruelly in the sun. Too sharp. Too clumsy. Thrinaxodon had thin, delicate bones. He had seen the holotype in a Cape Town museum; twin cubs, their burrow brutally bisected, their tiny bones destroyed. If this one was intact, it would stay that way.

“Fetch me my tool wrap, will you?” he said. “I think this one needs a more delicate touch.”

The assistant clambered back out of the trench. “Yes boss,” he replied.

In the meantime, Kitching was left with his two most faithful tools; his hands. Tanned and calloused by years of hard work, he had grown to bear the sting of sediment under his fingernails. With gentle care he worked to extricate the cast from the surrounding earth, teasing the ground, coaxing the object until it sat quite comfortably in his grasp. There was no need for his tool wrap after all.

It was slightly larger than a rugby ball in size and shape, and remarkably heavy. He turned it over in his hands, feeling its weight and visualising how the tiny creature was curled up inside. Try as he might, he couldn’t shake the feeling that the cast was too big for just the one animal. Perhaps there were clutchmates in there, or a mother and hatchlings. The cast would have to be cracked to know for sure, Thrinaxodon’s precious rest disturbed.

“Hey!” a voice called. His assistant had returned. “You got it out with your hands?”

He hopped down into the trench and unfurled the leather tool wrap with a flourish, pulling a sharp chisel from one of its compartments.

“You do the honours,” he said, holding the tool out expectantly.

“No.”

“After all this you’re not gonna crack it?”

“No,” repeated Kitching, cradling the cast in his lap. “We’ll take it back to the lab. X-ray it or something.”

The assistant sat down beside him in the dust. “An x-ray? Through solid sandstone?”

Kitching sighed. “Well, we’ll put it in storage. The technology will catch up.”

“Jim,” he replied, giving a thin half-smile. “The technology won’t catch up, not in my lifetime or yours. Could you really live with not knowing?”

Kitching rose to his feet, placing the fragile cast up on the lip of the trench. “Fetch the plaster wrappings. I want it crated up safe.”

“You’re the boss,” his assistant groaned.

The Karoo

The Triassic, 250,000,000 BC

It didn’t take long for the very worst of the noonday sun to pass. Broomistega whiled away the hours in the pool with only the tip of her snout above water, in that pleasant space between waking and dreams where everything feels just right in the world. When the Lystrosaurus herd spoke, she listened to them; little dramas of the herd so utterly foreign to a solitary roaming beast.

One of the sows had begun to grow anxious as the hours passed, rising from her sitting-place and pacing nervously along the shore. Broomistega had felt the ripples her footsteps made roll through the water.

The sow was gravid, apparently, and egg-bound from dehydration. Subject to mad hunches that such beasts would call a mother’s intuition.

“I just know something awful is coming,” she would say, over and over again. “Can’t you feel it? The ground is rumbling!”

Her sisters had tried to soothe her, but from where she lay in the cool green depths Broomistega knew that she was right. There was a rumbling, she could feel it deep in the marrow of her jawbone if she pressed it hard against the earth. It was peculiar, and very subtle; the soft thunder of faraway footfalls. Somewhere, a spectral herd was on the move.

The rest of the herd had grown anxious, snorting and shuffling and remarking quite worryingly about the colour of the sky. Broomistega had surfaced then, opening one eye only to be met by a deep grey overhead. A part of her hoped it heralded the coming of rain, but another part, a little pebble of ancestral dread in the back of her throat, knew that this was something more. She turned to the old boar for reassurance, but he was pawing at the dead earth with restless foreboding in his dark eyes.

Then came the trickle, a thin stream of black water that came snaking down the banks of the river. Broomistega knew something was terribly wrong when the gravid sow descended thirstily upon it, coming away wretching and spluttering. When it hit the pool, it instantly tainted its waters, burning the wound in Broomistega’s side. She sprung from it with a jolt and stood shaking on the shore, taking heavy breaths as the herd shared nervous glances.

There was silence, very briefly.

Then, inevitably, it came. A wall of liquid night many metres high, roaring like thunder and sweeping everyone off of their feet. As a creature of the water Broomistega could keep herself righted in the chaos, though blinded and stinging in the waves. The heavy Lystrosaurus were not as lucky. Their screams were heard only in the briefest of snatches as they were swallowed up.

Ragdoll limp, they were carried at breakneck speed downriver, knocked against every obstacle as they went. Feeling the scratch of thorns against her underbelly, Broomistega saw her chance. She closed her claws tightly around whatever it was she had been buffeted against, anchoring herself to it. Blindly, she scratched her way out of the blackness, landing in a choking heap on the high slope of the ruined riverbank.

She blinked the sediment from her swollen eyes, her vision cloudy. It was a long-dead bush that had been her salvation, now blackened and streaked with slime. But she wasn’t alone. Slowly, she turned her head to face her compatriot.

Beside her, bound by thorns, was the front half of Moschorhinus; white eyes stark against blackened fur. It had been wounded, dashed hard against rocks, and its hind half had vanished. Its exposed entrails glistened with sickly lustre.

Broomistega gave a shriek of terror, brushing the body with a foot. Moschorhinus convulsed, its cracked lips trying desperately to form words.

An utterance escaped its mouth in a thin whine. “Help…”

Broomistega shook herself free from the thorn bush and bolted, scaling the steep bank slope on panicked claws. But in her haste, she couldn’t quite see where she was going. Her footing fell away beneath her, sending her tumbling quite unexpectedly into darkness.

For an awful moment she thought she’d fallen back into the floodwater, but she swiftly found herself still and dry, and safe upon a mat of soft moss. She looked upwards, the angry grey of the sky visible through a circular hole. It was a burrow.

She sighed gratefully, only to meet a stranger’s gaze. Two amber eyes blinked open, lit like waning moons.

“You’re muddy,” they said. “Something bad has happened, hasn’t it?”

Broomistega trembled in the low light.

The stranger stepped forward. She was a Thrinaxodon; velvet-furred, with a broad wet nose. She arched her back and yawned, stretching out clawed forepaws.

“Black water,” Broomistega gibbered. “It came and…”

Thrinaxodon sighed. “A mudslide?”

Broomistega gulped, finding her throat raw. “The Lystrosaurus all got swept away. Moschorhinus was…”

Thrinaxodon nudged softly at Broomistega’s cheek, her nose leaving a wet mark behind. “Don’t get upset. You sit down here, with me.”

Thrinaxodon turned, pointing to the rear chamber of the burrow with her nose and ushering Broomistega to follow. It was pleasantly cool in the shadowy depths, though the air was stale with the scent of sweat and wet fur. Broomistega laid down upon a pile of moss, but a lingering hesitance stopped her from closing her eyes.

She frowned furtively. “Why are you being kind to me?”

Thrinaxodon gave a slow blink. “Why should I be cruel?”

“We are the same size,” Broomistega stammered. “If it came to blows, we’d both die.”

Thrinaxodon laid down beside her. She rested her head on her soft front paws and shut her eyes. “Then we won’t come to blows.”

Broomistega shut her own eyes, but then quickly opened them again. The rushing waves outside were steadily growing louder. The beast was almost at their door.

“Is this burrow high enough? We won’t flood, will we?”

Thrinaxodon rolled onto her side. “It has always been safe before.”

Then, just like that, the wall began to droop. A chunk slid away, hitting Thrinaxodon’s back with a worryingly wet shlop. Slowly, the ceiling was sinking inwards.

“I don’t want to die,” Broomistega whispered.

She registered a change in Thrinaxodon’s breathing. Quick, shallow breaths. The heaving of her chest was heavy at her side.

“I… Can’t you swim?”

A thin trickle of liquid snaked down through the burrow’s entrance, followed by a tide of wet mud. The hole was collapsing. There really was no more going back.

“In freshwater,” Broomistega replied, blind in the sudden immense darkness. She found herself drawing closer to Thrinaxodon’s body, her warm-bloodedness utterly foreign yet somehow still comforting. “But the black water burns my eyes, and I have a wound in my side.”

“I can’t either,” Thrinaxodon exhaled, her breath warm against Broomistega’s skin. “So, I guess…”

“It’s not fair! I’m not… I’m not even grown yet! I didn’t think I was gonna… for years and years!”

Thrinaxodon exhaled mournfully, pulling her forepaws close to her chest. “Death doesn’t spare the young, little one,” she sighed. “I had cubs, once.”

“I’m sorry, I… I must sound terribly selfish, I… Didn’t mean…”

“No, no. I’m not offended. I don’t feel sad for them anymore. Wherever they are, I know they aren’t hurting,” Thrinaxodon said, moving her head only to recoil when it made contact with the pooling water. “I’ve dug up a lot of old bones in my time. Not once has one complained.”

Broomistega snorted in surprise, inhaling the bitter fluid. She hacked harshly, and then gave a whimper. The joke had been a glittering moment of freedom, a distraction bright like the sun. And then, just like that she was back. Dying again.

“I’d always hoped I’d get home,” she croaked. “To the spawning lake, where the others are. Like me. So I could be known and loved and… And find peace.”

“I am a stranger to you,” Thrinaxodon whispered. “And as far from your kind as there is. But I can love you if you want me to, and maybe you could love me, just for a while.”

Broomistega felt the ghost of a smile creep across her face. Though the growing waters lapped bitterly at the wound in her side, something warm and giddy fluttered in her stomach.

“Oh. Well, I guess I love you,” she said.

Thrinaxodon gave a little laugh. “I guess I love you, too.”

“And if we’re found here, our bones,” Broomistega continued. “Then… Then we won’t complain, will we?”

Her partner’s laugh was fraught with weakness. “No, we won’t.”

Not one more word was said in the intimate dark.

The last thing Broomistega knew was a sort of soft weightlessness, her body pinned by the tide against the back wall of the burrow. Salt and sediment rushed briefly over her tongue, the water pushed into her nose and mouth and through her needle teeth. Gently, eternity crept in, her sweet stranger still at her side.

ESRF Laboratory, Grenoble, France

The Anthropocene, 2012 AD

The unassuming stone arrived at the lab in a box marked T. liorhinus. Its finder had kept it under wraps until his passing, and then it had gone forgotten; still unprepared in its crate and plaster casing. The day of the palaeontologist-adventurer, wild frontiersman with only his intuition to guide him, had similarly long been lain to rest. Now, in this realm of white tile and gleaming metal, it was the turn of Synchrotron’s all-seeing eye to penetrate the ancient past.

With careful hands, the specimen was placed on its side in a broad grey barrel. It was buried in a bed of dense sediment; a canvas of homogeneity from which the great machine could extricate intricate detail. The barrel was then sealed, perhaps just a little ignobly, with a ring of duct tape around its lid.

For hundreds of hours, it sat on the altar, sliced digitally by the rays of a germanium sun into strata mere microns thick. Each slice was studied by the great computer, teasing apart bone from rock and bone from bone.

There, translucent and illuminated on the computer screen, was the promised Thrinaxodon; curled up as sweetly as a little dog by the fire, every bone in her delicate frame as true as it ever was in life.

But there was a surprise at Thrinaxodon’s side. Kept safe in Thrinaxodon’s embrace for a quarter-billion years, was the little amphibian Broomistega; wounded but still very much whole.

Beloved strangers, delivered by their finder’s mercy, ready to be seen by the world at last.

Critical Commentary

The bare bones of Even in Another Time originated in the summer of 2022, when I first encountered images of the fossil known colloquially as “The Triassic Cuddle”2 on social media. Intrigued by its striking appearance, I followed the images to their source; an article from the journal PLOS ONE3 that documents both the process of Synchrotron microtomography that was used on the specimen, and discussion over its origins.

The specimen is a burrow cast; a type of fossil created when sediment-rich water rapidly fills an animal’s burrow during flooding or mudslide, which is hardened to sedimentary rock through time and pressure4. The rapid death of the animal, combined with the lack of scavengers and weathering deep underground, results in highly intact specimens that often maintain lifelike articulation; their posture potentially indicating their behaviour in life.5 Historically, these fossils were only accessible by physically cracking them open, damaging the remains and disturbing their articulation. However, recent imaging techniques such as Synchrotron microtomography allows for three-dimensional renderings to be made non-invasively. The original specimens are left intact, and the resulting computer graphics can be digitally disarticulated to study the specimen in greater depth.6

Though this specimen, discovered in 1975 by the South African palaeontologist James Kitching, was only originally believed to contain the remains of Thrinaxodon liorhinus7 (a transitional reptilian cynodont who possessed many mammalian features such as specialised teeth, the lack of lumbar ribs,8 and whiskers that may possibly indicate a full coat of fur9), imaging conducted in 2012 at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility revealed the body of Broomistega putterilli (a primitive semi-aquatic temnospondyl amphibian10) as a co-inhabitant of the burrow. Though there is evidence of Triassic animals exhibiting burrow cohabitation within the same species,11 and the juveniles of some modern extant amphibian species are occasionally encountered as interlopers in the burrows of other animals12, two Triassic animals of dramatically different species sheltering together in this manner is considered incredibly unusual.13

The paper from PLOS ONE hypothesises that Thrinaxodon was either aestivating or freshly dead by the time Broomistega took shelter in the burrow. Though Broomistega possessed extensive injuries, including broken ribs and bite marks, these are considered beyond the extent of which the similarly sized Thrinaxodon could inflict. The two animals had no meaningful interactions with each other, and may not have even noticed each other’s presence in the burrow.14

Despite this scientific consensus, I was struck by the visual symbolism of the fossil; two disparate animals in what appears to be a loving embrace. This formed the seeds of the narrative in my head; a story built on artistic licence where these two creatures really did know and care for each other.

This concept took several forms throughout the development process. My initial idea, which was pitched during the early meetings with professors, was to use the story as an environmentalist parable; using the End Permian Extinction Event15 (an incident often dubbed “The Great Dying” that saw a large percentage of life on Earth destroyed16) as a backdrop on which to construct an allegory for the modern-day climate crisis. The two creatures finding a love for each other would serve as a metaphor for the type of solidarity and love that humanity would have to find in order to overcome our own problems.

However, research into the Triassic era revealed that the two creatures were not casualties of the great extinction, but struggling survivors in the new world that followed it;17 small, hardy, and intensely adaptable animals whose lineages would continue on for far longer.18 Though I would permit many inaccuracies in the course of my project, I would not allow this rather large one, and I was compelled to rework my idea.

My second idea, bearing far more resemblance to the story that would eventually come into fruition, was an anthropomorphised xenofiction story in the same realms as the works Richard Adams19. The anthropomorphised characters would be more than metaphors for humanity, requiring more realised characters, and an environment that was if not realistic, appropriately verisimilitudinous

I started this process of development from the setting outwards. Studying the works of palaeontologist Peter D. Ward20 revealed to me that the environment of the Karoo has changed remarkably little across the eons; a “. . . lost world . . .”21 that is “. . . far from anywhere in time and space . . .”22 Though its name means “land of thirst” in the language of its indigenous people,23 it is a place of many weather conditions; from blistering drought24 to sudden flood.25 I discovered that flash floods of the sort that likely killed Broomistega and Thrinaxodon26 were of particular danger there; the dry ground unable to absorb sudden onslaughts of water27.

Though the modern Karoo is a hub of surprising biodiversity, home to “. . . springbok, eland, reebok, zebra, and the more lumbering gemsbok, bontebok, wildebeest, and kudu. . .”28, I struggled to research more than a handful of species who lived there during the immediate aftermath of The Great Dying. One animal, the small therapsid herbivore Lystrosaurus, was so greatly benefitted by the sudden death of almost all of its competitors that it became the most prolific animal of its environment, its species representing 95% of the fossils discovered in what once was its habitat.29

As a result, the landscape I present in my story is a touch anachronistic. Though the hardy seed fern Glossopteris would continue to be a dominant feature of the landscape into the Triassic30, the watering hole ecosystem at their base is decidedly more Permian-influenced in its vitality31. I chose to portray it this way because I enjoyed the storytelling potential that the waterhole setting offered; observing living animals using a similar watering hole on a live-stream from Namibia,32 predator and prey alike engaged in a tense sense of truce around the precious resource, occasionally devolving into scuffle.

The first completed draft of my story utilised a heavily mythological framing. I was inspired by the rabbit religion presented by Richard Adams within Watership Down33; stories about the rabbit hero El-ahrairah34 that are used by the characters both to provide context to their suffering, and as a source of strength in a world that would otherwise make perpetual victims out of them.

In a similar fashion, my draft revolved around a set of cosmological beliefs held by Broomistega; that the world was contained within a giant egg (with oviparity being a unifying feature between all land vertebrates before the evolution of viviparity35), with the sun as its yolk. The animals of the world, all brothers and sisters in spirit, live their lives in service of bringing the world to some perfect finished state, whereupon the egg would hatch, bringing about a state of enlightenment where every suffering that ever occurred would be vindicated and mourned, and every joy celebrated. Broomistega had an extended discussion with Thrinaxodon while trapped in the burrow regarding Thrinaxodon’s own experiences. As a digging animal, Thrinaxodon frequently encounters the bones of other animals. To her, they are just refuse; life and death having no greater purpose, and suffering ultimately pointless in the face of oblivion. Dying, Broomistega promises Thrinaxodon that their lives do have meaning, a belief that is then vindicated through a final scene that depicted the scanning of the fossil.

Though this version was completed, I ultimately decided that this incarnation of the story was not particularly effective. With over half of the story taking place in a featureless dark burrow, the pacing seemed to grind to a halt in service of dialogue that ultimately ended up with an unnecessarily maudlin tone. Retaining the most effective aspects of this draft; Broomistega’s interactions with a Lystrosaurus herd, and the ending featuring the fossil being scanned; I decided to distance myself from actively writing for a while, and returned to research to help formulate a new approach.

At this stage, I had already learned all I needed to about the Triassic period, and I found myself drawn to the process of palaeontology itself. I began to research James Kitching, the man who discovered the fossil in 1975, and passed away in 200336 before the truth about its contents could ever be brought to light. I found myself struck by an anecdote from his youth; that he, as a small boy, was already finding fossils for the renowned Scottish palaeontologist Robert Broom (for whom Broomistega was named37).38

After failing to find scholarly sources that verified this story, I realised that it is likely to be apocryphal. Though they were colleagues as adults39, the sponge fossil Kitching allegedly discovered named “Younopsis kitchingi”40 may not actually exist. However, like the many other artistic licences I have taken in the creation of my work, I decided to utilise this tale in the construction of a fictional narrative.

However, my characterisation of Kitching does originate in some truth. Kitching did oppose the physical destruction of specimens in the pursuit of study, with his work imaging sauropsid dinosaur eggs with an electron microscope demonstrating the ways in which fragile specimens could be investigated with only minimal invasion.41

This injection of a human element into my story altered my overall theme from a spiritual one to one more humanistic in nature. It is not some cosmic egg that sees Broomistega and Thrinaxodon displayed before the world; but mercy, thoughtfulness, and forward-thinking in the face of opposition. Just as Thrinaxodon chooses kindness and comforts Broomistega in the burrow, the fictionalised Kitching chooses kindness by not damaging the specimen even if it means that he will never see the results of his work. Though the two approaches are different, they have the same effect on the narrative; the death of the animals is elevated from more than mere tragedy to something that feels substantive and meaningful. Only, this new approach achieves this goal in a way more interesting than just dry discussion.

The main challenge with this new approach was balancing the two plot threads I had created. I realised that potential readers may not have encountered the story of the fossil before, which encouraged me to be thoughtful with the order in which information is revealed. I purposely placed the vignette where Kitching discovers the fossil ahead of the scene where Thrinaxodon is introduced as a living character in order to invoke a sense of doom; though the reader knows logically that the Triassic characters are already long dead by the time the Anthropocene scenes take place, ordering the scenes in this way helps create a better sense of how their fates are intertwined. This also helps partially conceal one of the greatest shortcomings of the story, the fact that these new plot threads necessitated Thrinaxodon’s role in the story be cut down. Though I am happy with many aspects of this story, I can admit that Thrinaxodon’s segment comes across as rather rushed.

Though I am reasonably proud of the work I have created given the circumstances, I must confess that these have been the roughest circumstances I have encountered during my degree. Though I started this project very strongly at the onset of the module, a health issue at the start of this year provided a disruption to my studies. As many things in my life suddenly became rather difficult, I struggled to maintain my previous momentum, and progress diminished greatly, including having to miss my presentation due to a medical incident. Though I feel what I have created is satisfactory, it is unfortunate that much of my research had to be streamlined for time, including my more theoretical research about the concept of anthropomorphism within literature that remains visible in my bibliography yet unfortunately underexplored in my project.

However, conducting this project has still been a rewarding experience, and I come away from it not only with rudimentary knowledge in a field previously foreign to me, but a show of my own resilience under pressure. Though I have perhaps diverted from the type of research expected from a creative writing project, I have uncovered a newfound passion for writing about extinct fauna, and I hope this is a topic that I can follow in future works.

Bibliography

Abdala, F., J. C. Cisnesros, and R. M.H. Smith. “FAUNAL AGGREGATION in the EARLY TRIASSIC KAROO BASIN: EARLIEST EVIDENCE of SHELTER-SHARING BEHAVIOR among TETRAPODS?” PALAIOS 21, no. 5 (October 1, 2006): 507–12. https://doi.org/10.2110/palo.2005.p06-001r.

Abram, David. The Spell of the Sensuous : Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World. New York: Vintage Books, A Division Of Penguin Random House Llc, 1996.

Adams, Richard. Watership Down. London: Rex Collings Ltd, 1972.

Attenborough, David. Life on Earth. London: William Collins, 2018.

Black, Riley. “A Triassic Cuddle Set in Stone.” National Geographic, March 3, 2014. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/a-triassic-cuddle-set-in-stone.

Blackburn, Julia. Dreaming the Karoo. Jonathan Cape, 2022.

Blakemore, Erin. “Fossil Study Challenges Assumptions about the ‘Great Dying.’” Washington Post, February 18, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/science/2023/02/18/fossils-china-great-dying/.

Botha, Jennifer, and Roger M. H Smith. “Lystrosaurus Species Composition across the Permo-Triassic Boundary in the Karoo Basin of South Africa.” Lethaia 40, no. 2 (April 8, 2007): 125–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1502-3931.2007.00011.x.

Broom, Robert. The Mammal-like Reptiles of South Africa and the Origin of Mammals. Surrey: H. F. & G. Witherby, 1932.

Cowgill, Ethan. “Safe beneath Extinction?” www.youtube.com, March 19, 2016. https://youtu.be/4CSOGf2YQfQ.

Crist, Eileen. Images of Animals: Anthropomorphism and Animal Mind . 1999. Reprint, Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2010.

Day, Michael. “Charting the Fossils of the Great Karoo: A History of Tetrapod Biostratigraphy in the Lower Beaufort Group, South Africa” 48 (December 1, 2013): 41–47. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309533063_Charting_the_fossils_of_the_Great_Karoo_A_history_of_tetrapod_biostratigraphy_in_the_Lower_Beaufort_Group_South_Africa.

Dillard, Annie. Teaching a Stone to Talk : Expeditions and Encounters. Internet Archive. New York : Harper Perennial, 1992. https://archive.org/details/teachingstonetot00dill/page/n3/mode/2up.

Erwin, D. H. “The End-Permian Mass Extinction.” Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 21 (1990): 69–91. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2097019.

Fernandez, Vincent, Fernando Abdala, Kristian J. Carlson, Della Collins Cook, Bruce S. Rubidge, Adam Yates, and Paul Tafforeau. “Synchrotron Reveals Early Triassic Odd Couple: Injured Amphibian and Aestivating Therapsid Share Burrow.” Edited by Richard J. Butler. PLoS ONE 8, no. 6 (June 21, 2013): e64978. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0064978.

Fernandez, Vincent, and European Synchrotron Radiation Facility . “Vincent Fernandez - Digging Virtually into Large Fossils Using Synchrotron X Ray Microtomography.” www.youtube.com, December 16, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fn2Qup0kTfo.

Foster, Charles. Being a Beast : Adventures across the Species Divide. New York: Metropolitan Books, Henry Holt And Company, 2016.

Groenewald, G. H., J. Welman, and J. A. Maceachern. “Vertebrate Burrow Complexes from the Early Triassic Cynognathus Zone (Driekoppen Formation, Beaufort Group) of the Karoo Basin, South Africa.” PALAIOS 16, no. 2 (April 1, 2001): 148–60. https://doi.org/10.1669/0883-1351(2001)016%3C0148:vbcfte%3E2.0.co;2.

Halliday, Thomas. Otherlands. Random House, 2022.

Holleman, Marybeth. “Other Nations.” In Writing for Animals: New Perspectives for Writers and Instructors to Educate and Inspire, 143–56. Oregon: Ashland Creek Press, 2018.

Jasinoski, Sandra, and Fernando Abdala. “Aggregations and Parental Care in the Early Triassic Basal Cynodonts Galesaurus Planiceps and Thrinaxodon Liorhinus.” PeerJ 5 (January 10, 2017): e2875. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.2875.

Kitching, James , and Frederick Grine. “Scanning Electron Microscopy of Early Dinosaur Egg Shell Structure: A Comparison with Other Rigid Sauropsid Eggs.” Scanning Microscopy 1, no. 2 (December 19, 1986). https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2266&context=microscopy.

Lomax, Dean, and Robert Nicholls. Locked in Time. Columbia University Press, 2021.

Lovegrove, Barry. Fires of Life : Endothermy in Birds and Mammals. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019.

MacMahon, A. G, and J. P Swart. “The Laingsburg Flood Disaster.” Sa Mediese Tydskrif 63 (May 28, 1983): 885–86.

Marshall, C. R., and D. K. Jacobs. “Flourishing after the End-Permian Mass Extinction.” Science 325, no. 5944 (August 27, 2009): 1079–80. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1178325.

Mindat. “Broomistega Putterilli ✝.” www.mindat.org. Accessed January 24, 2023. https://www.mindat.org/taxon-P266420.html.

NamibiaCam, and The Gondwana Collection. “Namibia: Live Stream in the Namib Desert.” www.youtube.com, November 30, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ydYDqZQpim8.

Nesbitt, Sterling , Julia Desojo, and Randall Irmis. Anatomy, Phylogeny and Palaeobiology of Early Archosaurs and Their Kin. London: Geological Society, 2013.

Paige, Madison, and The Embryo Project. “James William Kitching (1922-2003) | the Embryo Project Encyclopedia.” embryo.asu.edu. Arizona State University, July 3, 2018. https://embryo.asu.edu/pages/james-william-kitching-1922-2003.

Patrick, Sean, Ross Damiani, Sean Modesto, and Adam Yates. “Barendskraal, a Diverse Amniote Locality from the Lystrosaurus Assemblage Zone, Early Triassic of South Africa Miocene and Late Oligocene Faunas View Project Johann Neveling Council for Geoscience Barendskraal, a Diverse Amniote Locality from the Lystrosaurus Assemblage Zone, Early Triassic of South Africa,” January 2003. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/289119722_Barendskraal_a_diverse_amniote_locality_from_the_Lystrosaurus_Assemblage_Zone_Early_Triassic_of_South_Africa?enrichId=rgreq-816b5980fb79a2063154f922308408bc-XXX&enrichSource=Y292ZXJQYWdlOzI4OTExOTcyMjtBUzoxMTM2MDAxOTE3NDM1OTA0QDE2NDc4NTUzNzEwNzc%3D&el=1_x_2&_esc=publicationCoverPdf.

Prevec, Rosemary, André Nel, Michael O. Day, Robert A. Muir, Aviwe Matiwane, Abigail P. Kirkaldy, Sydney Moyo, et al. “South African Lagerstätte Reveals Middle Permian Gondwanan Lakeshore Ecosystem in Exquisite Detail.” Communications Biology 5, no. 1 (October 30, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-022-04132-y.

Prothero, Donald R. The Story of Life in 25 Fossils Tales of Intrepid Fossil Hunters and the Wonders of Evolution. Columbia University Press, 2015.

Raath, Michael, and Bruce Rubridge. “James William Kitching 1922-2003 - a Tribute,” 2005. https://www.academia.edu/64214585/James_William_Kitching_1922_2003_a_tribute.

Recknagel, Hans, Nicholas A. Kamenos, and Kathryn. R. Elmer. “Evolutionary Origins of Viviparity Consistent with Palaeoclimate and Lineage Diversification.” Journal of Evolutionary Biology 34, no. 7 (June 24, 2021): 1167–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.13886.

Sappho, Anne Carson, and Jenny Holzer. If Not, Winter : Fragments of Sappho. London: The Folio Society, 2019.

Smith, Julie A, and Robert W Mitchell. Experiencing Animal Minds : An Anthology of Animal-Human Encounters. New York: Columbia University Press, 2012.

Smith, Roger M. H. “Sedimentology and Ichnology of Floodplain Paleosurfaces in the Beaufort Group (Late Permian), Karoo Sequence, South Africa.” PALAIOS 8, no. 4 (August 1993): 339. https://doi.org/10.2307/3515265.

Ugueto, Gabriel N. Ecteninion Lunensis. April 17, 2017. Online image. Twitter. https://twitter.com/serpenillus/status/852591804558053376?lang=zh-Hant.

Ugueto, Gabriel N. Tetracynodon Darti and Moschorhinus Kitchingi. February 18, 2018. Online image. Twitter. https://twitter.com/SerpenIllus/status/964515321582374913/photo/1.

University of Witwatersrand. “HONORARY GRADUATE James William Kitching.” wits.ac.za, n.d. https://www.wits.ac.za/media/wits-university/alumni/documents/honorary-degree-citations/James%20Kitching.pdf.

Ward, Peter D. “Abrupt and Gradual Extinction among Late Permian Land Vertebrates in the Karoo Basin, South Africa.” Science 307, no. 5710 (February 4, 2005): 709–14. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1107068.

Ward, Peter D. Gorgon: Paleontology, Obsession, and the Greatest Catastrophe in Earth’s History. New York: Viking, 2004.

Ward, Peter D. On Methuselah’s Trail : Living Fossils and the Great Extinctions. New York: W.H. Freeman, 1992.

1 Sappho, Anne Carson, and Jenny Holzer, If Not, Winter : Fragments of Sappho (London: The Folio Society, 2019), 297.

2 Riley Black, “A Triassic Cuddle Set in Stone,” National Geographic, March 3, 2014, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/a-triassic-cuddle-set-in-stone.

3 Vincent Fernandez et al., “Synchrotron Reveals Early Triassic Odd Couple: Injured Amphibian and Aestivating Therapsid Share Burrow,” ed. Richard J. Butler, PLoS ONE 8, no. 6 (June 21, 2013): e64978, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0064978.

4 G. H. Groenewald, J. Welman, and J. A. Maceachern, “Vertebrate Burrow Complexes from the Early Triassic Cynognathus Zone (Driekoppen Formation, Beaufort Group) of the Karoo Basin, South Africa,” PALAIOS 16, no. 2 (April 1, 2001): 148–60, https://doi.org/10.1669/0883-1351(2001)016%3C0148:vbcfte%3E2.0.co;2, 153-4

5 Fernandez et al., “Synchrotron Reveals Early Triassic Odd Couple: Injured Amphibian and Aestivating Therapsid Share Burrow.”

6 Vincent Fernandez and European Synchrotron Radiation Facility , “Vincent Fernandez - Digging Virtually into Large Fossils Using Synchrotron X Ray Microtomography,” www.youtube.com, December 16, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fn2Qup0kTfo.

7 Fernandez et al., “Synchrotron Reveals Early Triassic Odd Couple: Injured Amphibian and Aestivating Therapsid Share Burrow.”

8 Donald R Prothero, The Story of Life in 25 Fossils Tales of Intrepid Fossil Hunters and the Wonders of Evolution (Columbia University Press, 2015),255

9 Prothero, The Story of Life in 25 Fossils,” 266

10 Dean Lomax and Robert Nicholls, Locked in Time (Columbia University Press, 2021), 157

11 F. ABDALA, J. C. CISNEROS, and R. M.H. SMITH, “FAUNAL AGGREGATION in the EARLY TRIASSIC KAROO BASIN: EARLIEST EVIDENCE of SHELTER-SHARING BEHAVIOR among TETRAPODS?” PALAIOS 21, no. 5 (October 1, 2006): 507–12, https://doi.org/10.2110/palo.2005.p06-001r.

12Lomax and Nicholls, Locked in Time, 160

13 Fernandez et al., “Synchrotron Reveals Early Triassic Odd Couple.”

14 Fernandez et al., “Synchrotron Reveals Early Triassic Odd Couple.”

15 D. H. Erwin, “The End-Permian Mass Extinction,” Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 21 (1990): 69–91, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2097019.

16 Erwin, “The End-Permian Mass Extinction,” 74-5

17 Fernandez et al., “Synchrotron Reveals Early Triassic Odd Couple.”

18 Peter D Ward, Gorgon: Paleontology, Obsession, and the Greatest Catastrophe in Earth’s History (New York: Viking, 2004), 110

19 Richard Adams, Watership Down (London: Rex Collings Ltd, 1972).

20 Ward, Gorgon.

21 Ward, Gorgon, 10

22 Ward, Gorgon, 10

23 Ward, Gorgon, 10

24 Ward, Gorgon, 52

25 Ward, Gorgon, 23

26 Fernandez et al., “Synchrotron Reveals Early Triassic Odd Couple.”

27 Roger M. H. Smith, “Sedimentology and Ichnology of Floodplain Paleosurfaces in the Beaufort Group (Late Permian), Karoo Sequence, South Africa,” PALAIOS 8, no. 4 (August 1993): 339, https://doi.org/10.2307/3515265.

28 Ward, Gorgon, 12

29 Sean Patrick et al., “Barendskraal, a Diverse Amniote Locality from the Lystrosaurus Assemblage Zone, Early Triassic of South Africa Miocene and Late Oligocene Faunas View Project Johann Neveling Council for Geoscience Barendskraal, a Diverse Amniote Locality from the Lystrosaurus Assemblage Zone, Early Triassic of South Africa,” January 2003, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/289119722_Barendskraal_a_diverse_amniote_locality_from_the_Lystrosaurus_Assemblage_Zone_Early_Triassic_of_South_Africa

30 Thomas Halliday, Otherlands (Random House, 2022), 182-3

31 Rosemary Prevec et al., “South African Lagerstätte Reveals Middle Permian Gondwanan Lakeshore Ecosystem in Exquisite Detail,” Communications Biology 5, no. 1 (October 30, 2022), https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-022-04132-y.

32 NamibiaCam and The Gondwana Collection, “Namibia: Live Stream in the Namib Desert,” www.youtube.com, November 30, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ydYDqZQpim8.

33 Adams, Watership Down.

34 Adams, Watership Down, 37-40

35 Hans Recknagel, Nicholas A. Kamenos, and Kathryn. R. Elmer, “Evolutionary Origins of Viviparity Consistent with Palaeoclimate and Lineage Diversification,” Journal of Evolutionary Biology 34, no. 7 (June 24, 2021): 1167–76, https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.13886, 1170

36 Michael Raath and Bruce Rubridge, “James William Kitching 1922-2003 - a Tribute,” 2005, https://www.academia.edu/64214585/James_William_Kitching_1922_2003_a_tribute.

37 Barry Lovegrove, Fires of Life : Endothermy in Birds and Mammals (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), 70

38 University of Witwatersrand, “HONORARY GRADUATE James William Kitching,” wits.ac.za, n.d., https://www.wits.ac.za/media/wits-university/alumni/documents/honorary-degree-citations/James%20Kitching.pdf.

39 Madison Paige and The Embryo Project, “James William Kitching (1922-2003) | the Embryo Project Encyclopedia,” embryo.asu.edu (Arizona State University, July 3, 2018), https://embryo.asu.edu/pages/james-william-kitching-1922-2003.

40 Paige, “James William Kitching (1922-2003) | the Embryo Project Encyclopedia,”

41 James Kitching and Frederick Grine, “Scanning Electron Microscopy of Early Dinosaur Egg Shell Structure: A Comparison with Other Rigid Sauropsid Eggs,” Scanning Microscopy 1, no. 2 (December 19, 1986), https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2266&context=microscopy.