I don’t remember all that much from the crash. It has always been said that the meds they give you to sleep through intersolar travel are so strong that you could sleep through the apocalypse. And in a way, I think I did. My own apocalypse, that is. I am under no illusion that I will be rescued.

I was ripped from oblivion by a bitter, choking cloud of unpleasantness. Blinded, throat burning, coughing through goodness knows what. The sort of heat that feels like it could carbonise flesh and then crystallise carbon. Systems whirring to compensate for descent, to protect my soft little body, and then being shredded for their efforts with an awful scream.

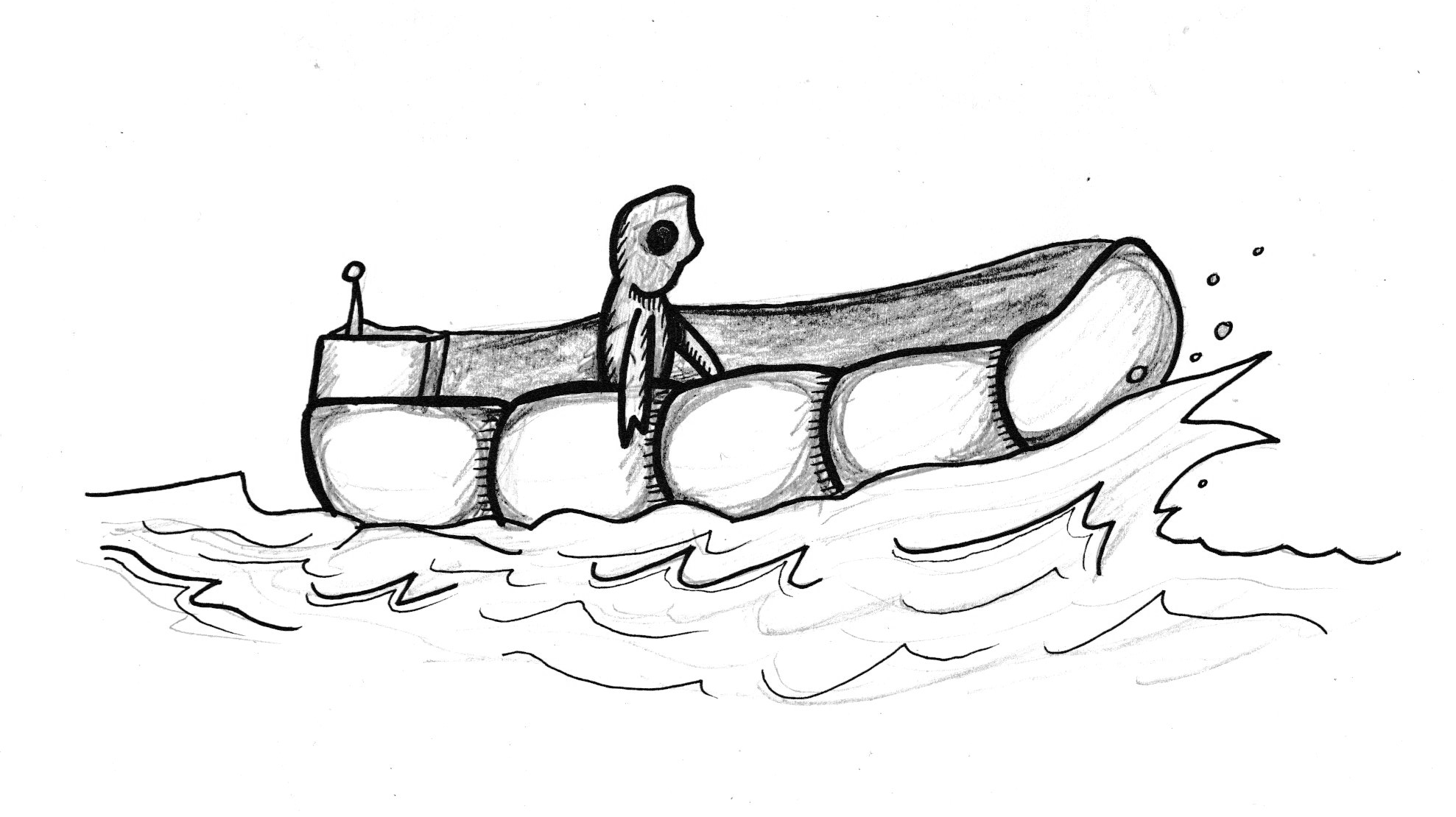

And then salt water. A new and strangely familiar stinging in the eyes, like childhood trips to the seaside. A rush of air, and the squeal of plastic. A vibrant yellow life raft puffing into life from the wreck of the ship’s hold and catching me like a gigantic welcoming hand.

I blinked away the ash, and the sky that met my vision was a brilliant, cloudless blue.

The one-man sleeper craft I had rented to take me from Hemera to my new job on Elpis was in pieces in the water all around me, and I was adrift at sea goodness knows where.

The rations they put in these things leave a lot to be desired. To fit everything a person needs for weeks and weeks in a space the size of a lunch box means that everything has to be packed pretty tight, and taste is the last of anyone’s concerns.

There were a few bags of vacuum-sealed water potability tablets. I skimmed some ocean water into a concave shred of scrap metal and dropped one in to dissolve. It had that sort of aggressively citrus scent they use in cleaning products meant for grimy public bathrooms, and it tasted like bleach because that’s basically what it was. The gathered up salt and toxins left a sort of crusty scum on the bottom of my makeshift bowl.

Food. Dozens of palm-sized brown squares wrapped in plastic. They had something a bit like this on the homeworld called pemmican, I think. Three-thousand calories a square; fats and carbs and sugars rendered down into their crudest forms and pressed into a miserable little roof tile to feed the ravenous. I took my first primal gnaw of a bite, and it almost took my front teeth away with it.

A solar cell charged an autonomous navicomputer at the raft’s rear, connected to a motor that could steer the craft in the direction of something resembling land. All I had to do was sit back and tend to my wounds, which were numerous.

Okay, perhaps I couldn’t complain too much. I was burned in places, and half of the hair I’d spent years preening was singed down to the scalp, but I had my life. I gathered some water in my makeshift bowl and dropped in some more tablets so I could wipe myself clean, hissing like a stuck cat as my hands passed over raw forearms and shoulders.

The nights were so dark and so long that I thought I couldn’t possibly loose track of how many days it had been. But sleep did not come easily to me, an animal used to stillness cast upon the sickly swaying of the sea. In and out and in and out of naps and nights and hours. Six days, perhaps. Or six squares of food, since one square was about a day’s provisions. /p>

One morning, and I’m sure it was morning, the raft got caught on craggy black rocks and tore. I stirred from yet another fruitless attempt at a nap and cursed at it. But when I threw my arm out over the edge to fill my bowl, I made contact with sand and sediment. The shallows.

And there it was. Land.

I got out of the raft and dragged it through the knee-height water, and then collapsed onto a beach of grey-blue sand.

Solid ground. I remember this sensation distinctly, because it was unlike anything I’ve ever felt; my body so used to the rhythm of the ocean that the ground was almost swaying beneath my feet.

I ate two squares in a ravenous haze, and then curled up on the sands and collapsed into sleep. True sleep, for the first time.

My clothes were ripped and my skin was raw and naked. I was sunburned from shoulder to tail bone by the time I woke up.